By Arin Pereira

'It is a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma,' so Winston Churchill referred to Russia in 1939. In 1996, Russia is a different place, but the reserve of mystery remains, at least in Moscow. Its exteriors can be wildly deceiving, and, like native Matryoshka dolls, the city nestles together, layer upon layer in a series of rings. It was constructed that way, and even the traffic flows in circles; there are no left turns allowed.

At the center of Moscow's inner circle lies the Kremlin, Russia's mythic refuge and symbol of centralized power. In Russian the word kreml means 'fortress,' but this Kremlin is more than that. It is a city-within-a-city, where a multitude of magnificent palaces, churches, famous squares and armories create a magical, golden onion-domed skyline.

Its outside walls are 7,319 feet long, 65 feet high, and 20 feet wide. It has four gates and 19 towers, dominated by the great gilt dome of the Ivan Great Belltower. It also houses the Tsar Cannon and Bell, both the largest of their kind in the world, and neither ever worked. About half the Kremlin's interior is off-limits to tourists, including the Arsenal, the Senate, and the State Kremlin Palace, but there is still much to see.

At the Troitsky Gate Tower entrance, a medieval drawbridge leads up into the massive red-brick citadel. The moat is now dry, but walking the bridge feels like stepping through time. I made my first unforgettable trip to the Kremlin with my brother, who lives in Moscow and whose fluent Russian made Moscow more accessible, as it is not exactly English-friendly. (Before going, it is a good idea to learn the Cyrillic alphabet.)

We started at the Armory, which costs about $15 to enter. Moscow museums all seem to have a two-tier fee system which translates into something like a 1000 percent surcharge for foreigners. Its collection of Imperial armor is astounding, but even more so the gold, silver and jewels collected over the centuries by various rulers, including dozens of Faberge easter eggs, jewelled thrones, and royal coaches.

In the costume room, visitors can see the likes of Boris Gudonov's armor, Peter the Great's boots and long narrow-shouldered coats, the diamond encrusted mantles of the great Patriarchs of the Russian Orthodox Church, and the coronation robes of Catherine the Great.

The Diamond Fund exhibit is also in the Armory, but the $40 entrance fee disinclined me to gaze upon what must be one of the world's greatest collections, including the 190-carat Orlov diamond.

Cathedral Square is the Tsarist heart of the Kremlin. Crowded around it are the great palaces and cathedrals. Cathedral of the Assumption, the oldest and most important, is a renaissance masterpiece where the city's bishops and Patriarchs were interred. Cathedral of the Annunciation, once a private church for Russian princes, contains magnificent iconostases by Theofar the Greek and Andrei Rubliov, and its floor is tiled with agate and jasper. Cathedral of Archangel Michael is where the Tsar's were buried until Peter the Great relocated the capital to St. Petersburg in 1712. Until then, the Terem Palace, oldest building in the Kremlin, served as the Imperial residence. The Faceted Palace was used for audiences and feasts, and the Great Kremlin Palace, (where the President lives now), was built in the 19th century as a residence for Nicholas I. None of the Kremlin palaces are open to visitors yet.

Red Square abuts the Kremlin to the northeast. Lenin's Tomb, a sort of sleek massive marble sarcophagus, is planted there. Inside, it is dark, and a series of graded walkways decorated with bizarre, red marble thunderbolts take visitors past the embalmed corpse of Lenin, arranged with an extended hand and looking like wax. Ironically, Moscow's great GUM shopping center, a paragon of capitalist values, sits directly across from the Tomb.

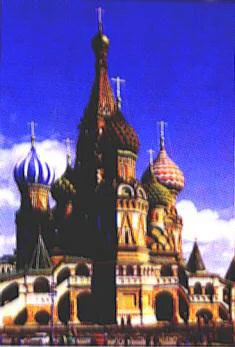

Moscow's most familiar emblem, St. Basil's Cathedral, is also on Red Square. Built by Ivan the Terrible in 1552 to commemorate victories over the Tatars, it is a colorful Oriental jewel. Reputedly, Ivan had its architects blinded to prevent them designing anything like it again. Inside St. Basil's, a series of small, dark, irregular chambers are linked by exquisitely painted passages. Leaving St. Basil's, reeling with its beauty, I looked across Red Square at the gates to the Kremlin and was reminded of an old Russian proverb: 'There is nothing above Moscow except the Kremlin and nothing above the Kremlin except Heaven.'

Underground Moscow is also worthy of adage. Gilded domes and marble floors reflect the soft light thrown by crystal chandeliers; bronze statuary and colorful mosaics tell stories from myth and history; great halls arch above sweeping staircases, punctuated by delicate carved railing: This is the Moscow Metro.

One of Stalin's pet projects, the stations were conceived of as a sort of people's palace, each unique, some spectacular. Preeminent Soviet architects and artists collaborated, and the project was started in 1932. The stations can be strangely incongruous with the rather colorless, weary crowds I saw bustling through-the magnificent architecture and decoration an ironic glaze over the tedium of life. It is a fast, efficient system, however, carrying more than 8 million commuters each day. A one-way, flat fare token (zheton) costs about 35 cents. All signs are in Cyrillic, so it is a good idea to purchase a guide in English. I took the metro many times, at all times of the day-it runs from 5:30 a.m. until 1 a.m.-and found it much easier than trying to get through the horrendous traffic in any other way. The tourism group Patriarchi Dom offers a very good guided tour of the system, and there is even a Museum of the Metro at the Sportivnaya Station.

I was most impressed by the mosaic representations of Russian national heroes and Soviet soldiers marching across the ceiling of the Novokuzenetska Station, and by the Ploschad Revolutsii Station where dozens of Socialist-realist bronze figures bloom larger than life from every column, glorifying the worker, in all shapes from ironworker to infantryman.

One night we took the metro to the ballet because we did not want to be late. My sister-in-law had procured front center balcony seats for a performance of Sleeping Beauty at the Bolshoi Theatre (literally 'big' theatre). After checking our coats and drinking a glass of Russian shampanskoye in the lobby bar, we took our seats on the top tier 'balkon.' From there, perched on slim velvet chairs, we got a full view of the ornate red and gold splendor of the inner theater itself.

Built in 1824, the building's grand Ionic facade hides a neglected interior. Like elsewhere in Moscow, the building and the dancers suffer from privation. The company was started in 1773 as a dancing school for the Moscow Orphanage and has retained a very traditional repertoire. The Bolshoi acoustics are excellent, and the performance I saw was highly theatrical with rich costumes and lovely music.

Tickets to a Bolshoi performance actually cost about 50 cents, but it is difficult to buy them at face value. They are bought up by legitimate agencies and racketeers weeks before performances and resold to foreigners at enormous profit, usually at about 50 times their actual cost. Touts sell tickets outside the popular venues, or they can be bought at the theatre kiosks (Teatralnaya Kassa) located near most metro stations. There is a good one in front of the Intourist main office on Manezhnaya Ploschad.

For a different sort of Russian experience, we went one night for dinner at Mama Zoya's, a well known Georgian restaurant. Georgians are known for their love of music and food, (wine and women, too), and the restaurant did not disappoint.

The entrance to Mama Zoya's is through a rough, wooden door in the corner of an inner courtyard. A short, narrow staircase leads guests below ground as rich odors waft up accompanied by a melancholy voice singing with guitar. The smoke overwhelmed us as a seedy, velvet curtain was pulled back to reveal the restaurant itself. Low ceilings and shabby carpets enhanced the sinister feel. The music stopped. We were eyed with suspicion and only grudgingly served a bottle of excellent Georgian wine while we waited to be seated. Everything was red: the wallpaper, the table linens, the carpeting, the plates, our waiter's eyes... Suddenly, amid the dark looks, smoke, and rich smells, the guitarist broke into song and the entire room lost interest in us. We felt collective relief and ordered an enormous meal, some of almost everything on the menu washed down with lots of Georgian wine. The food was delicious and tasted Mediterranean with lots of garlic and herbs, tasty cheese bread (khachapuri), meat dumplings (palmeni), and eggplant (baklazhan). The bill came to about $30 for five of us.

The next day, feeling somewhat the effects of the large meal, I ventured to a real Russian bath, or banya, the Sandonuvskaya at Pervy Neglinny Pereulok. The banya is a tradition in Russia and nothing like the spa experience in the United States-not yet, at least. First of all, the bathhouses I saw were all rather rundown. Second, they are inexpensive, about $3 for the whole day. You buy the famous switch of birch (veniki) from a vendor stationed near the bathhouse entrance.

After leaving all clothing in your assigned vestibule (leave valuables at home), you take a shower and soak your veniki. Then you enter either the dry sauna or the steam room for as long as you can stand it, switching yourself (and your neighbor, if she asks) with the birch as the pores open. I went with another American woman and her adolescent daughter. The Russian women knew we were foreigners because we did not cover our hair. They were all wearing gummy woolen caps to protect theirs and told us ours would fall out.

At first, we were eyed with suspicion, although my friend speaks Russian. But the women slowly came around to us as we withstood all forms of birchbeating, turned blazing pink, and shuffled dutifully from dry to steam sauna then into the cold pool without a whimper. We ended up sharing laughs and feeling part of the big, maternal Russian group.

'You are brave for American girls,' one of the women informed us, 'not so soft as we thought.'

Most bathhouses also offer splendid massage services, and some have onsite estheticians for facials, manicures, and pedicures. It is a thoroughly rejuvenating experience.

Moscow has been going through its own rejuvenation over the past five years. 'It's vitality and chaos are a direct result of the collapse of communism and the efforts of its citizens to reinvent their lives,' according to one travel authority.

Religion, the Marxist 'opium of the people,' is making a comeback, including newer religions, such as Mormonism, which some Russian women find attractive for its abstinence approach, (there is a lot of heavy drinking in Russia).

Construction is taking place everywhere, most spectacularly in the resurrection of many of the great churches that Stalin destroyed or converted. He had one of the finest, turned into a public swimming pool.

I did not find Moscow a particularly friendly place, but it did not seem dangerous either. When I was there, the painful effects of economic transition were most apparent in the large number of old people, pensioners, selling their belongings on the streets to help meet the costs of living. Perversely, there is also a glamorous, obviously monied group of Muscovites who drive around in expensive cars and wear designer jewels and clothing.

The city seems to function on at least two distinct levels; then again, like the Matryoshka dolls, there are surely many not evident at first glance. It will take more trips to Moscow to even begin to solve its riddles.

Getting There

I flew Finnair to Moscow, through Helsinki. The current advance purchase ticket price is about $1100. The supersaver fare from Sept. 16-Oct. 31 is $908 weekday/$968 weekend. In November, fares go down to $798/$848. The flight from New York is impeccable and the food delicious. Finnair also offers special rates at the Hotel InterContinental in Helsinki, a lovely city where a three-day sojourn on the return trip is a good way to reacclimate and relax. Call Finnair for details at (703) 534-7512 or (800) 950-0500.